The Memoir of the Le Fanu Family

(Extracts)

The privately printed memoir of the Le Fanu family written by Thomas Philip Le Fanu was ‘based on materials’ collected by William Joseph Henry Le Fanu ‘scholar of Trinity College Dublin, distinguished Indian civil servant and accomplished linguist’. The following extracts trace the history of the family from its early flourishing in Normandy in the mid-seventeenth century through the religious persecution of the Huguenots following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes to their ‘second home’ in Ireland initially as exiles but soon assimilated into the Anglo-Irish ascendency.

Table I and Table II from the Memoir (click each to view detail)

The origin of the name Le Fanu is doubtful. There is another Norman name occurring much more frequently and differing only by one letter which denotes a personal peculiarity. This is Le Canu, in mediaeval Latin Canutus, meaning white-haired Man. This suggests a possible connection with fenutio, defined by Du Cange as equivalent to ruber color. The meaning of the name would then be “redhead” or “redcoat”. It has also been suggested that it may be a Scandinavian place name, though the termination of the Latin form Fanutus does not favour this derivation. There is an island Fano to the south-west of Jutland, and there is also a Fano in Norway. It has again been connected with the Norse and Danish word Fane, signifying a standard or banner, but these are mere guesses.

After these attempts to peer into the remote past, there is more than a touch of bathos in the confession that, save for a single reference, nothing whatever is known of the family before the middle of the sixteenth century: An ecclesiastical record of the year 1415 refers to one Abbé Le Fanut. But the Le Fanu pedigree, so far as it can now be traced, begins one hundred years later with Michel Le Fanu who took his degree in arts at the University of Caen in 1536. All the leading members of the learned professions at Caen appear to have been connected with the University. The spirit of the renaissance and the new learning had in many cases attracted them to the reformed religion which, in France more than either in England or Germany, was especially indebted to the Universities for its advancement. There is reason to believe that in the middle of the sixteenth century the majority of the professors of the University were Huguenots. Many of these professors, who were also busy men of the world taking their full part in the affairs of their city, amused themselves in their lighter hours by the composition of verses, sometimes in French but more often in Latin, the universal language of the learned. Of Michel Le Fanu and his son Etienne, Jacques de Cahaignes writes as follows: -

“Michel Le Fanu était entraîné par une vocation naturelle vers l’étude de la poësie; mais comme il voyait qu’elle n’était d’aucune ressource pour le soutien de sa famille, et que la moisson du poëte etait nulle, les vers ne servant qu’à vous charmer et non a vous nourrir – il s’appliqua à l’étude du Droit Civil, bien que ce ne fût pas son penchant, et se destina ou barreau. Tout le temps que lui laissaient ses occupation judiciares il le consacrait aux Muses, ses amies de prédilection. A vrai dire, il improvisait ses ver latins et français plutôt qu’il ne les composait. Chez lui facilité égalait l’inspiration; tout sujet, quelque aride et quelque futile qu’il fût, était pour lui une occasion de montrer les ressources inépuisables de son imagination.”

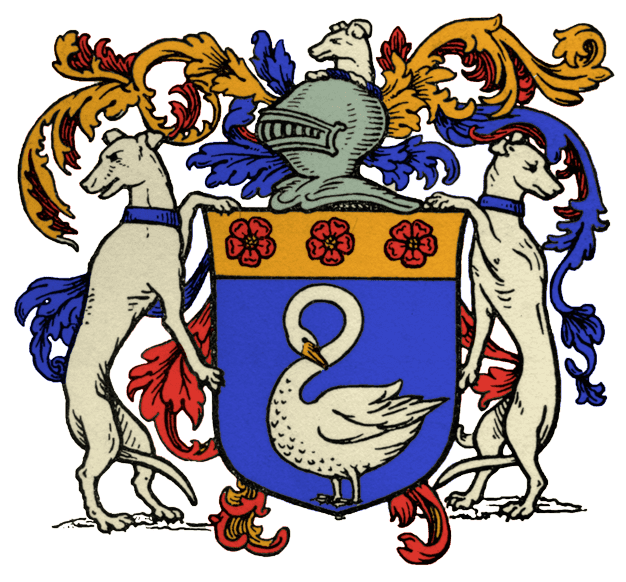

In spite of the rival claims of poetry, Michel Le Fanu devoted himself with success and distinction to the practice of the law from 1543 until his death in 1576. He acted as Counsel for the city of Caen in the action brought against it in 1553 by the inhabitants of Rouen and the other free towns of Normandy, and was apparently investing in land from 1554. His son, Etienne Le Fanu’s chief claim to be remembered by his descendants arises from the part which he took in the stirring affairs of his time and his services to Henry IV, by whom he was ennobled in 1595. The original Titre de Noblesse then given into his hands was discovered in 1911 inn use as the cover of a book in the library of a Norman monastery which had recently been dissolved. The arms, “D’azur, au cygne d’argent; au chef d’or chargé de trois roses de geules fleuronnées d’or” are emblazoned in the centre of the parchment with two greyhounds as supporters and for crest a greyhound’s head.

The document thus describes Etienne Le Fanu’s services:–

“Il n-avait obmis aucun point de devoir et fidellité ... qui touche notre service et le bien publicq speciallement au t emps le plus turbulant et lorsque nos enemis se sont efforcez de nous desrober le coeur de nos bons et loyaulx subjects outre lesquels services qui mériteraient bien de nous une bonne recompense, il nous a encore en ces jours passez secouru d’une bonne somme de deniers pour subvenir au paiement des Suisses de notre armée, suivant notre edict du mois d’octobre mil cinq cent quatre vingt quatorze wui est un evident tes moignage de l’extrême affection qui’il a en notre service, au moien de quoy il merite aultant que nul autre estre retenu par nous au nombre de ceux que nous avons resolu d’anoblir par notre dit edict.”

Etienne’s notable grandson (also) Etienne was born in 1625 and was thrice married. In 1656, being then thirty-one years old age, he fell in love with a Roman Catholic lady, Mademoiselle Catherine Le Blais de Longuemare and conforming for the occasion to the faith of his bride, abjured the reformed religion and was married by a Roman Catholic priest. For this he was summoned within less than a year before the consistory when he made public acknowledgement of his fault and promised to bring up his children in the reformed religion. His efforts to carry out this promise brought him into conflict with his wife’s relations and ultimately led to his trial and imprisonment. A contemporary account records:

The mother of his children dying, although by the custom of the country the father hath the right of being guardian and tutor of his children yet most unjustly the relations of the deceased gentlewoman, who were all Papists got two judgements passed against him enjoining him to deliver up his children under the penalty of eight hundred livres French money. Being wholly governed by the Bishop of Bayeux and other of the Clergy and rigid papists this poor gentleman was made a prisoner, and at the taking of him they miserably abused him, beating him, tearing his clothes, breaking his sword, dragging him in a brutish manner through the streets and, in all probability had not a gentleman named the Viscount of Caen come by and took him into his coach and conducted him with his guard to the prison, he had been massacred by the bloody rabble.

Charles Le Fanu de Cresserons was one of the numerous refugees who escaped immediately before or after the revocation to Holland. While serving there he was saved, according to family tradition, by his soldiers, the waters of a canal having been let in upon them while he was sleeping in his tent. Joining the army of the Prince of Orange, he served during the Irish campaign as a captain in La Melonière’s regiment of foot having as a brother officer his first cousin, Jean Hellouin de Secqueville, who had escaped first to Alderney, and then to Holland. He fought at the battle of the Boyne in that regiment which was the first to ford the river at Oldbridge, and a portrait of William III, said to have been given to him by the King, is still in the possession of the family.

When aged fifty, Charles had been on active service almost without a break since he left France at about thirty years of age. Finding himself no longer equal to the hardships of a campaign, he retired from the army and settled down in 1710 in Dublin where he remained until his death on the 17th November, 1738. By his will, dated 23rd July, 1733, he left all his property in Ireland, England or France to his cousins, Philippe and Jacques Le Fanu.

Philippe and his family had moved to Dublin in 1730 and inherited from Charles a house and garden on the west side of St Steven’s Green.

His son, William Le Fanu prospered in the land of his adoption. He was a merchant and banker. The exact nature of his business is not known, but it appears from his will that he had a warehouse behind his house in the Green where he had wine stored, and he was granted a premium of £40 by the Linen Board inn 1749 for manufacturing or causing to be manufactured 203 and 606 yards of coarse linen.

His life appears to have been generally a peaceful one. Though the baptisms of several of his children were entered in the registers of the French Church which assembled in the Lady Chapel of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, he seems to have attached himself to his parish church, St. Peter’s, where he was married. He seems to have acquired considerable property. A list made out at the time of his death in 1797 includes lands in King’s County and Westmeath, houses in Anne Street, Francis Street, Fleet Street, lower Abbey Street and North Anne Street. He also had some interest in the Theatre Royal in Crow Street.

William had one daughter and eight sons. The daughter and three of the sons died young; all the sons, though apparently baptised by French names, used in later life their English forms. The eldest Philip won a scholarship at Trinity College, Dublin in 1753 and became in after years a Doctor of Divinity. Thomas, the second of five sons who lived to manhood, went into the army. The three further sons, Joseph, Henry and Peter all married into the Irish family, the Sheridans – see ‘the Sheridan connection’.

In 1990 William Le Fanu (1904-1995) wrote some notes supplementing the Le Fanu Family Memoir which, with an introduction, footnotes and genealogy by Julian Le Fanu, are available to read here.