Profiles of individuals

Index

- The Sheridan Connection

- The Very Revd Thomas Philip Le Fanu’s Burial Ground [90]

- Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu [98]

- William Richard Le Fanu [100]

- The Family of William Richard Le Fanu [100] and Henrietta Victorine Barrington [101]

- Henry Frewen Le Fanu [118]

- William Le Fanu [127]

- Elizabeth Maconchy [127a]

- Brinsley Le Fanu [128]

- John Lewen Le Fanu [129]

- Admiral Sir Michael Le Fanu [138]

- In Memoriam: Anthony Le Fanu [139]

- Henry Le Fanu [160]

- Cecil Le Fanu [178]

- Roland Le Fanu [181]

- Sir Victor Le Fanu [193]

The Sheridan Connection

The Sheridan Connection on Ancestry

All Le Fanus share two common ancestors, the successful banker and merchant William (Guillaume) Le Fanu three of whose sons, Joseph, Henry and Peter married three granddaughters of the Anglican divine and poet, the Reverend Thomas Sheridan – Alicia and Elizabeth Sheridan and their cousin Frances Knowles. The circumstances surrounding this tripled forged alliance by marriage between the third generation of the Huguenot Le Fanus in Ireland and one of their country’s oldest established families are described in the following two extracts – the first from Linda Kelly’s biography of Richard Brinsley Sheridan and, second, the introduction to Betsy Sheridan’s journals edited by William Le Fanu.

Linda Kelly

Richard Brinsley Sheridan: A Life

Sinclair-Stevenson (1997)

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

The Sheridans, or O’Sheridans as they were originally called, were one of the oldest families in Ireland: the earliest O’Sheridans were said to have arrived from Spain in the fifth or sixth century, founding an abbey on Trinity Island, in the little archipelago of lakes and islands between the towns of Cavan and Killeshandra. A sketchy but more specific family tree, preserved in the Chief Herald’s Office in Dublin, begins in 1013 with the marriage of Ostar O’Sheridan, of Togher Castle, owning ‘many great possessions in the County Cavan ... as far as to the borders of the Counties of Meath, Westmeath and Longford, too many and needless to be made mention of’, to the daughter of the O’Rourke, Prince of Leitrim. It continues, unhampered by further dates, with the names of other Gaelic chieftains with whom the Sheridans were intermarried: the Princes of Sligo, Longford, Cavan, Tyrone and the O’Conor Don – a remote but glorious roll-call which remained a source of pride to their descendants.

By the end of the seventeenth century the Sheridans’ estates, like the princedoms, had dwindled away. But they still held their rank amongst the respectable gentry of Cavan and, having converted from Catholicism earlier in the century, belonged to what was later called the Protestant Ascendancy. Politically their loyalties were mixed, a few remaining faithful to the Catholic James II at the time of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. One member of the family, Thomas Sheridan, formerly Secretary for Ireland, followed the king into exile as his private secretary; his brother William, Bishop of Kilmore, was deprived of his see for refusing to take the oath of allegiance to William III.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s grandfather, the Reverend Dr Thomas Sheridan, is described as a ‘near relation’ of these two, probably a first cousin once removed. He was a scholarly, unworldly man, uninterested in politics, but with a strain of quixotry in his character that echoed theirs. ‘You cannot make him a greater compliment,’ remarked Dean Swift, ‘than by telling him before his face ... how careless he was in anything relating to his own interests or fortune.’ it was a characteristic his grandson would inherit.

Dr Sheridan is best remembered as Swift’s bosom friend. He was a clergyman and schoolmaster, for many years the head of Dublin’s leading school – ‘doubtless the best instructor of youth in these kingdoms and perhaps in Europe,’ in Swift’s opinion, ‘and as great a master of the Greek and Roman languages’. The classical plays his pupils put on were famous, emptying the professional theatre on the evenings they took place. Swift took lessons for his friend when Dr Sheridan was ill, and he delighted in the doctor’s cheerful, witty company. they shared a taste for puns and humorous, often scabrous, verse and once exchanged poems daily for a year, on their honour not to spend more than four minutes writing them. It was at Quilca, Dr Sheridan’s small estate in Cavan, that Swift completed Gulliver’s Travels.

The introduction to

Betsy Sheridan’s Journals

edited by William Le Fanu

Elizabeth “Betsy” Sheridan

Betsy Sheridan grew up in a wandering life without a settled home. She was born in Henrietta Street, Covent Garden in 1758. Her father Thomas Sheridan [son of the Reverend Dr Thomas Sheridan] had been a successful actor-manager in Dublin till his theatre was wrecked in a political riot in 1756. His attempt to establish himself as an actor in London was thwarted by the pride which made him refuse contracts and insist on profit sharing. With Garrick at the height of his popularity there was no room for an actor who would not take second place. Garrick in spite of his easy pre-eminence was always jealous of rivalry. In London he had his place in literary society, entertained Johnson and Boswell, and knew many of the people with whom Boswell’s assiduity has made us all familiar. Boswell professed to like Thomas Sheridan, but he reports the many unkind and unjust things which Johnson said of him. In consequence, Johnson’s characterisation ‘Sherry is dull, naturally dull’ has stuck to his memory. Betsy’s picture of her father is partial on the other side, and she gives us the idea of a generous, intelligent person, kindly to her and sensible in ordinary affairs, though peevish and ill-tempered from illness and failure, and peculiarly obtuse and bitter in his relations with his sons.

When his theatre was wrecked and his fortune disappeared with it, he had had to give up the fine house he had built for himself in the fashionable north side of Dublin and to mortgage his little country place, Quilca in Co. Cavan, where Swift had stayed with his father. His affairs were taken in hand by friendly trustees, the first of whom was a Huguenot merchant and banker, William Le Fanu, who had come to Dublin as a young man and prospered in the close-knit Huguenot community which played a large part in the business and professional life of Dublin in the reign of George II.

The Huguenots were readily assimilated in Anglo-Irish society, into the world of officials, lawyers, and clergymen trained at Trinity College. They were not puritans; strict in religious observance and their sense of social duty, they enjoyed the good things of civilisation. Such were the sons of Thomas Sheridan’s trustee and banker ‘good Mr Le Fanu’. The eldest and youngest sons were clergymen; between them came Joseph who married Alicia Sheridan and Henry who married Betsy, the writer of the Journal. Joseph held a post in the Irish customs office but was chiefly interested in books and the theatre. He was a young widower with a boy of eight when he married Alicia in 1781. It was probably their shared interest in the theatre which drew him and Alicia together, for she alone of his children inherited her father’s love of acting. Joseph and Alicia both acted for many years in the amateur theatre which the Dublin Huguenots supported.

Henry Le Fanu is a shadowier figure than his brother. He was a Captain in the 56th Foot and had distinguished himself at the siege of Gibraltar in 1779, but when Betsy met him at her sister’s house he was a half-pay officer with a small allowance from his father. She had thirty years of happy but never prosperous married life and lived on as a widow till she was seventy-nine. [The third of the Le Fanu sons to marry into the Sheridan family, the Reverend Peter Le Fanu was a fashionable preacher and rector of St Brides Church in Dublin. He married Frances Knowles whose mother Hester was the daughter of the Reverend Dr Thomas Sheridan and father was John Knowles some time treasurer of Thomas Sheridan’s Dublin theatre.]

Back to Index

The Very Revd Thomas Philip Le Fanu’s Burial Ground [90]

excerpts from the Abington burial register

provided by Philip Dee

The LeFanu Stone, Graveyard of St John and St Ailbe’s Church, Abington, Co. Limerick

The LeFanu stone is most likely a grave marker originally fixed in the wall of the churchyard at Abington to mark the burial ground or enclosure of the Very Revd Thomas Philip Le Fanu (1784-1845) (90), Dean of Emly and, from 1823 until his death in 1845, Rector of Abington. The Burial Register enables us to work out with almost certainty who was buried in the Dean’s enclosure.

Catherine, the Dean’s eldest child by his wife Emma Lucretia Le Fanu (née Dobbin) and sister of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu and William Richard Le Fanu, was the first to be buried in the enclosure. She died aged 27 on 25th March 1841 and was buried four days later. Jane Fergusson, the Dean’s sister-in-law, was next to be buried there. She was followed by Maria Knowles (daughter of the Dean’s second cousin, James Sheridan Knowles), who died aged 26 and was buried on 16th June 1844. The Dean’s entries in the Register for these burials are laconic masterpieces of sorrow and acceptance.

The Dean died on 20th June 1845 aged 61 and was buried three days later. In 1861 he was joined by his widow, Emma Lucretia, who had died aged 78.

Catherine LeFanu

Buried in the churchyard of Abington, Catherine Frances LeFanu, only daughter of the Very Revd. T.P. Lefanu, Dean of Emly and Rector of Abington, and Emma Lucretia his wife. Sunday 29th March 1841. T.P. Lefanu.

My beloved child was born on the 7th June 1813 and God took her to himself on the 25th March 1841. The funeral service was read at my request by the Revd. Michael Lloyd Apjohn, Curate of Dromkeen.

Maria Knowles [and reference to Jane Fergusson]

Buried in the Church yard of Abington Maria Knowles aged 26 years – daughter of my cousin, James Sheridan Knowles, Esq., 16th June 1844. T.P. Lefanu.

The funeral service was conducted by Revd. Thos Atkinson. She is deposited in my own burial ground next my dear sister-in-law, Jane Fergusson and within the same enclosure my darling and only daughter. The will of the Lord be done.

Very Revd. T.P. LeFanu

Buried in the church yard of Abington, the Very Reverend Thomas P. Lefanu, Dean of Emly and Rector of Abington who died 20th June 1845 aged 61 years. 23rd June 1845. Thomas Atkinson, Rector of Doon.

Emma Lucretia LeFanu

Emma Lucretia relict of the Very Rev. T.P. Lefanu, Dean of Emly and Rector of Abington, aged 78 years, buried in Abington church yard by me, A. MacLaughlin, Rector.

[Undated entry – entry #122 in the Burial Register: entry #121 was dated 14th March 1861 and entry #123 was dated 7th Oct 1861]

Back to Index

Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu [98]

Introduction from ‘The Illustrated J. S. Le Fanu’, Selected and Introduced by Michael Cox, Equation 1988

(with permission of the Publisher)

Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

‘Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’, wrote S.M. Ellis in 1916, ‘retains his own special place and fame as the Master of Horror and the Mysterious’. Today, his reputation is as high as ever amongst connoisseurs of supernatural fiction ... Amongst these, it was M.R. James who first appreciated and described the peculiar blend of qualities that placed Le Fanu, in his opinion, ‘absolutely in the first rank as a writer of ghost stories ... nobody sets the scene better than he, nobody touches in the effective detail more deftly’.

The Le Fanus were of Huguenot descent: one of them – Charles de Cresserons, a name Le Fanu was to use as a literary pseudonym – had fought for William of Orange at the Battle of the Boyne. By the eighteenth century they had become established as solid, respectable members of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy. But there was also a more volatile, literary and histrionic strain in the family, for Le Fanu’s grandmother on his father’s side was a sister of the dramatist Richard Brinsley Sheridan: these opposite qualities are apparent in Le Fanu, in whom predictability and enigma, conservatism and erratic brilliance, mingled.

In July 1811, JSL’s father, Thomas Le Fanu, married Emma, the daughter of Dr William Dobbin, rector of Finglas on the outskirts of Dublin. They began their married life at 45 Lower Dominick Street in Dublin, where their first child, Catherine, was born in 1813. The following year, in August 1814, JSL was born in the same house, though his earliest memories were of the Hibernian Military School in the Phoenix Park, to where the family had moved in 1815 when Thomas Le Fanu was appointed Chaplain.

In 1826 the family moved to Abington in Co. Limerick, Thomas Le Fanu having been appointed rector there. Beyond the civilised confines of the glebe house and its library, discontent and violence among the native Catholic population also fed into the imagination of the young Le Fanu, producing a lasting image of the Great House under siege and isolated, threatened by violent intrusions from an anarchic outer world. In W.J. McCormack’s words: ‘The essence of society as Le Fanu grew to know it in his Abington years was the isolation of his people from “the people”. In spite of the antagonism of the Irish to the political and religious allegiances of his class, Le Fanu nurtured strong nationalistic sympathies, as well as a deep admiration for the Irish people. He also derived imaginative sustenance from Irish folklore and legends, imbued as the majority were with a deep supernaturalism. How potent was the effect of these Limerick years, in particular the landscape of his boyhood and adolescence, can be seen for instance in this passage from the late story ‘The Child that went with the Fairies’ (1870) describing the haunted hill of Lisnavoura in the Slievefelim mountains:

A deserted country. A wide, black bog, level as a lake, skirted with copse, spreads at the left, as you journey northward, and the long irregular line of mountain rises at the right, clothed in heath, broken with lines of grey rock that resemble the bold and irregular outlines of fortifications, and riven with many a gully ... It was at the fall of the leaf, and an autumnal sunset threw the lengthening shadow of haunted Kisnavoura close in front of the solitary little cabin over the undulating slopes and sides of Slievefelim.

In 1832 JSL went up to Trinity College, Dublin, to read classics and train for the law. His first story appeared in the Dublin University Magazine in January 1838: ‘The Ghost and the Bonesetter’, the first tale in the collection posthumously entitled The Purcell Papers, named after the eponymous narrator, Father Francis Purcell. It was not long before writing began to assume a greater importance in his life than his legal studies. ‘Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter’ was published in the DUM in May 1930 (the year Le Fanu was called to the Irish Bar) and is the first of Le Fanu’s stories to hint at a synchronicity of the external themes of his fiction and personal disorientation. ‘Schalken’, a story of supernatural rape, is a variation on the demon lover theme, and though a certain ambiguity is conveyed by linking the climax of the story with Schalken’s dream, the whole thrust of the narrative is towards accepting the reality of supernatural intrusions. The death of his much-loved sister Catherine in March 1841 brought Le Fanu himself face to face with death for the first time, and from this date he began to show signs of morbidity and melancholy, coupled with the kind of religious and sexual anxiety reflected in ‘Spalatro’ (DUM, March 1843).

In December of that year Le Fanu married Susanna Bennett, daughter of George Bennett, QC, a leading barrister on the Munster circuit, who lived at 18 Merrion Square South in Dublin. Le Fanu took his bride back to Abington for Christmas, writing to his sister-in-law Elizabeth: ‘I think I never saw my father and mother take such a fancy to my dear little wife ... She is as merry as a lark, & for my part I am ten thousand times more in love with her than ever.’ Their first child, Elanor, was born in February 1845, followed by another daughter, Emma, a year later and a son, christened Thomas Philip, in September 1847.

In the New Year of 1851 Le Fanu published his first collection of stories, the now rare volume Ghost Stories and Tales of Mystery, containing ‘The Watcher’. ‘The Murdered Cousin’ (an early form of what was to become Uncle Silas), ‘Schalken the Painter’, and ‘The Evil Guest’.

The Le Fanus’ fourth child, George Brinsley Le Fanu, was born in August 1854. By this time the family had moved into the Bennetts’ house in Merrion Square. ‘An Account of Some Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street’, published in the DUM in December 1853, was Le Fanu’s last piece of fiction for nine years – a reflection of increasing domestic tension generated by debts, Susanna’s ill health, family deaths, and, in 1855, his brother William’s religious conversion, which threw into relief his own and Susanna’s spiritual doubts. The death of her father in May 1856 had a devastating effect on Susanna, who was already tormented by religious uncertainty and whose mental stability was threatened by a near hysterical reaction to death. As Le Fanu recorded: ‘If she took leave of anyone who was dear to her she was always overpowered with an agonizing frustration that she would never see them again. If anyone she loved was ill, though not dangerously, she despaired of their recovery.’

On 26 April 1858 Susanna herself was taken seriously ill. She died two days later. Le Fanu wrote immediately to his mother:

The greatest misfortune of my life has overtaken me. My darling wife is gone ... Pray to God to help me. My light is gone ... She was wiser than I & better & would have been to the children what no father could be ... She was the light of my life & light in every day.

Nelson Browne called the Le Fanus’ marriage ‘an exceptionally happy one’. It was not quite that. If Le Fanu was – as his brother William said – ‘devotedly attached’ to Susanna, there was also much anxiety, torment even, and negativity in the relationship. Of the extent of Susanna’s neurosis Le Fanu himself left a record:

She one night thought she saw the curtains of her bed at the side next the door drawn, & the darling old man [her father], dressed in his usual morning suit, holding it aside, stood close to her looking ten or (I think) twelve years younger than when he died, & with his delightful smile of fondness & affection beaming upon her ... [he said] ‘There is room in the vault for you, my little Sue.’

After his wife’s death Le Fanu became progressively more withdrawn and painful introspection became habitual. But in spite of these apparent disabilities he continued to write and in 1861 purchased the Dublin University Magazine, in which The House by the Churchyard was serialized in 1861-2 ...

This contains what S.M. Ellis considered to be ‘the most terrifying ghost story in the language’. Ellis’s verdict may be open to argument, but chapter ix, entitled ‘An Authentic Narrative of the Ghost of a Hand’, certainly illustrates Le Fanu’s ability to convey terror through a controlled and economic style that heightens the loathsomeness of the supernatural intruder:

He drew the curtain at the side of the bed, and saw Mrs Prosser lying, as for a few seconds he mortally feared, dead, her face being motionless,, white, and covered with a cold dew; and on the pillow, close beside her head, and just within the curtains, was the same white, fattish hand, the wrist resting on the pillow, and the fingers extended towards her temple with a slow wavy motion.

In the context of Le Fanu’s life, this incident – which is completely irrelevant to the plot, such as it is, of The House by the Churchyard – brings to mind Susanna Le Fanu’s disturbing dream of her dead father. What is generally regarded as Le Fanu’s masterpiece, Uncle Silas, appeared in 1864. His nephew, T.P. Le Fanu, suggested that the character of Austin Ruthyn was a sketch of the author himself: ‘It was a peculiar figure, strongly made, thick-set, with a face large, and very stern; he wore a loose, black velvet coat and waistcoat ... he married, and his beautiful young wife died ... he had left the Church of England for some odd sect ... and ultimately became a Swedenborgian’. And later, Maud Ruthyn is troubled by a vision of her dead father’s face – ‘sometimes white and sharp as ivory, sometimes strangely transparent like glass, sometimes hanging in cadaverous folds, always with the same unnatural expression of diabolical fury’. These correlations with actual personal trauma should remind us that Le Fanu was not a mere ‘sensationalist’ writing only for effect. His fascination – or even obsession – with the supernatural and the macabre coincided with embedded psychological characteristics, with dimensions of his nature that were linked to emotional disturbance and guilt.

Though Susanna’s death had encouraged Le Fanu’s naturally reclusive habits, and though he became known in Dublin a the ‘Invisible Prince’, he continued to keep in touch to a degree with the literary and political life of the city. Nor did the loss of his wife affect his writing output. After the purchase of the DUM in July 1861 he produced a succession of serialised novels for the magazine: The House by the Churchyard (1861-2), Wylder’s Hand (1863-4), Uncle Silas (1864), Guy Deverell (1865), All in the Dark (1866), The Tenants of Malory (1867), Haunted Lives (1868), and The Wyvern Mystery (1869).

JSL’s son, Brinsley Le Fanu gave the following celebrated account of his father’s solitary working habits in these last years:

He wrote mostly in bed at night, using copy-books for his manuscript. He always had two candles by his side on a small table; one of these dimly glimmering tapers would be left burning while he took a brief sleep. Then, when he awoke about 2 a.m. amid the darkling shadows of the heavy furnishings and hangings of his old-fashioned room, he would brew himself some strong tea – which he drank copiously and frequently throughout the day – and write for a couple of hours in that eerie period of the night when human vitality is at its lowest ebb.

At the end of January 1873 Le Fanu suffered an attack of bronchitis, though by the 31st he appeared to be recovering. He died on 7th February and was buried four days later in the Mount Jerome cemetery, in the Bennett tomb that contained his beloved Susan. His daughter Emma, in a letter to Lord Dufferin, remarked: ‘He lived only for us, and his life was a most troubled one’.

Back to Index

William Richard Le Fanu (1816-1894) [100]

William Richard Le Fanu

The senior branch of the Le Fanu family are all descended from William Richard Le Fanu. He was born in Dublin on 24th February 1816, the third and youngest child of Revd Thomas Philip Le Fanu, later Rector of Abington and Dean of Emly, and Emma Lucretia Le Fanu (née Dobbin). His elder brother was the novelist and ghost-story writer Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu.

W.R. Le Fanu became a railway engineer at a time of extensive railway building in Ireland. In ‘Seventy Years of Irish Life’ he wrote that his last ten years of practice as an engineer “were the busiest of my life. During them I was engineer to many railways and other important works, and so continued, with the additional duties of engineer to the Irish Light Railway Board, till 1863, when I was offered the appointment of Commissioner of Public Works in Ireland, which I accepted, having been much pressed to do so by my friends in the Irish Government” (p. 196). He was Commissioner of Public Works (a post his son Thomas Philip Le Fanu was also to hold) from 1863 to 1890, first as Second Commissioner and then as Chairman.

His grandson William Le Fanu wrote of him that he was “[r]eputed one of the most amusing and popular men of his time: a good ‘shot’ and the best salmon-fisherman in Ireland. A very close friend of his Sheridan cousins Caro Norton and Helen Dufferin and of Helen’s son, the famous diplomat and viceroy” (‘Notes supplementing T.P. Le Fanu’s family memoir’, ms, 1990). Stefanie Jones, writing in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, says “A friendly and outgoing man, he was a popular figure in Dublin’s social and literary circles, and had many prominent friends. Despite his many years working on Irish railways and as a public works commissioner, he was surprisingly better remembered as a ‘successful contributor to the contemporary literature of gossip and anecdote’ and as ‘a noted raconteur’ than as an engineer”.

He married Henrietta Victorine Barrington, daughter of Sir Matthew Barrington, 2nd Bt, in 1857. They had ten children, eight boys and two girls. He died on 8th September 1894 and is buried with his wife in the graveyard of St Patrick’s Anglican Church, Enniskerry. Their five unmarried sons and daughters are buried in two graves alongside theirs and Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s eldest daughter in a third.

Extract from the family memoir

by W.R. Le Fanu’s son Thomas Philip Le Fanu

(T.P. Le Fanu ‘Memoir of the Le Fanu Family’, privately printed, n.d., pp. 60-61)

Of William Richard Le Fanu it is unnecessary to say much. Most of the readers of this memoir will be familiar with his Seventy Years of Irish Life, and it is only necessary to observe with regard to that book that it records for the most part only the lighter side of a busy life. The first railway in Ireland, that from Dublin to Kingstown, was opened while he was still at Trinity College, and on completing his University course he became, in 1839, a pupil of Sir John MacNeill, the well-known civil engineer, having as a fellow pupil William McQuorn Rankine, afterwards the famous Professor of Engineering at Glasgow. The friendship of such a master of applied mathematics was of peculiar value in those days, when the theory and practice of engineering as applied to railway construction were in their infancy. For the next twenty-four years he worked as a civil engineer in Ireland, During that period practically all the main lines in Ireland were constructed, two of them, the Great Southern and Western and the Dublin, Wicklow and Wexford Railways, largely by his aid, and arterial drainage was also carried out to an extent not attempted in the country before or since. It was the busiest time that Irish engineers have known and his clear head, great power of concentration, and skill in managing both superiors and subordinates brought him to the head of the profession in Ireland. The obituary notice, written by his friend Charles Cotton, which appeared in the Journal of the Institution of Civil Engineers for 1895 , says: “As a railway engineer Mr. Le Fanu carried out many large and important works, though none were of such novel or striking importance as to call for special description. It is authoritatively stated that, so carefully were estimates prepared by him, that in no case was the amount exceeded which he advised as the capital to be provided. He was a well-known figure in the committee rooms while in private practice, no session passing without his having Bills to support or oppose.” In 1863 he was appointed a Commissioner of Public Works in Ireland. In that office he spent the remaining years of his working life, retiring in 1891 and dying on 8th September, 1894, the intervening years being in large part devoted to recording his recollections in the book already referred to.

William Richard Le Fanu

on the Catholic Agitations in Ireland

In retirement W.R. Le Fanu wrote ‘Seventy Years of Irish Life’ (Edward Arnold, 1893), being – as stated on the frontispiece – ‘anecdotes and reminiscences’. The book is hugely entertaining but also contains acute comments on the state of the country. Particularly interesting for many readers will be his description of life in Abington at the time of the Tithes War and biographical detail on Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu that is lacking in the latter’s own works. The final chapter touches on the ambivalence and tensions of being a Protestant Huguenot in Catholic Ireland.

CHAPTER XX

Catholic Emancipation, 1829 – The tithe war of 1832 – The great famine of 1846 – The Fenian agitation of 1865 – France against England – Land-hunger – Crime and combination – Last words.

As I have passed a long life, well over seventy years, almost altogether in Ireland, and have constantly come in contact with every class in the country, I conclude this book, on the present state of affairs, as seen by one who has personally observed the many agitations and the many changes in the condition of the country, which have occurred since the early part of the century.

The first great agitation which I remember was that for Catholic Emancipation, which was granted in 1829 under the pressure of a fear of an Irish rebellion. The great meetings and marchings had led the Duke of Wellington, then Prime Minister, to fear that Ireland was ripe for a rebellion, more serious than that of ’98, the danger and bloodshed of which he was unwilling to face.

My father and mother had been always ardently in favour of Catholic Emancipation, and were delighted when the Act was passed. On the night when the news that the bill had become law reached our part of the country, we were all assembled to see the bonfires which blazed on all the mountains and hills around us, and I well remember the shouting and rejoicings on the road that passed our gate, and the hearty cheers given for us. We little thought on that night how soon we should see the same fires lighted all around us, when any of the clergy near us had suffered outrage, or how soon, without any change on our part, we should be hooted and shouted at whenever we appeared ...

After the passing of the Emancipation Act comparative quiet reigned in the country till 1832, when the tithe war, with all its outrages, began. This agitation was carried out by O’Connell, on nearly the same lines as that for emancipation, and was crowned with like success. But the abolition of tithes did not bring to the peasantry all the benefits they expected; it merely changed the tithe into a rent-charge payable to the landlords, who were made liable for the payment of the clergy ...

Before the next agitation of any moment, the great famine of 1846-7 occurred. Up to that time the number of the people, and their poverty, steadily increased and the first change for the better in their condition, within my memory, was subsequent and, in a great measure, due to that terrible affliction. It put a stop in some degree to the subdivision of holdings which had been carried on to such an extent that, in many parts of the country, the holdings were so small that, even had they been rent free, they would have been insufficient for the maintenance of their occupiers. It forced the people not to depend in future on the potatoes as their staple food, and it led to some extent to better cultivation of the soil ...

For seventeen years after this time, no agitation worth recording arose and, with the exception of some isolated outrages, peace prevailed in the country and the prosperity of all classes increased. Then in 1865 the Fenian Society came into existence and continued to increase in power and in the number of members enrolled until, in February 1866, the Habeas Corpus Act was suspended ...

What I have called the principal Fenian army was, in reality, only a mob of half-armed and utterly undisciplined Dublin youths who had assembled near this village of Tallaght. When opposed by the small force of constabulary, who fired a few shots, they retired to a neighbouring hill. Many of them dispersed during the night, but a considerable number remained till the morning when they surrendered to a military force and were marched into Dublin. I did not myself see the prisoners but I remember my brother telling me how he had seen them, so tired out that, wet as it was, they were lying about on the ground in the Castle yard. My brother’s pantry-boy had joined the army but was one of those who escaped being made prisoner and he used to give a most interesting account of the Battle of Tallaght.

Looking back on those various agitations to which I have briefly referred, it appears to me that none of those which appealed merely to the anti-English sentiment of the people, ever obtained any real hold of the peasantry. Those which did succeed appealed to feelings of an entirely different nature, and aimed at the abolition of some religious inequality or some pecuniary burden, and there are few who would now deny the justice of Catholic Emancipation and of the abolition of the tithe system in Ireland.

I do not mean to suggest, by what I have just written, that the anti-English feeling is not a real thing. It is, on the contrary, as far as my observation goes, a very deep and far-reaching sentiment. Their chief hope has always appeared to lie in a successful rebellion, by the aid of America or, possibly, of France. Many of them have looked forward all their lives to “the War” as they call it. It is not long since a tenant of my brother-in-law, when on his death-bed, said to him, “Ah, yer honour, isn’t it too bad entirely that I’d be dying now, and the War that I always thought I’d live to see coming so near?” The strength of the feeling was shown by the wild burst of enthusiasm in favour of the French at the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War, when processions marched through Dublin and other town in Ireland, with tricolor banners, and led by bands playing the “Marseillaise”. This sympathy with the French was undoubtedly due to the tradition of the help that had been expected from France in 1798, and to the hope that, if necessary, help against England might again be obtained from the same quarter.

But, strong as this anti-English feeling is, it is not in it, as I think, that the real strength of the agitation of the last fifteen years has lain ... It was the uniting of the Land Question with the agitation for Home Rule which really roused the peasantry. It is impossible for any one who has not resided in Ireland, and been on intimate terms with the people, to realise the intense longing which animates them for the possession of land, no matter how small or how bad the holding may be. If a farm was vacant owing to eviction of the tenant or otherwise, there were always numbers ready to compete for it, and willing to pay the landlord a fine for its possession, far beyond its value. To this land-hunger was also due, to a great extent, the subdivision of farms, which was so ruinous to the country; for in former days the father of the family thought the best way he could provide for his younger sons was to give each of them some portion of his land ...

I have always believed it is the Land Question which is really at the root of the whole matter, and that it should be settled by some system of compulsory purchase to be determined upon and carried out by the Imperial Parliament, for it is difficult to imagine that such a question could be really fairly dealt with by a body of men elected almost entirely by the votes of one of the parties to the dispute.

It is unfortunately true that considerable religious animosity still exists which, though dormant, is ready to break out on any provocation; but I cannot see how these feelings would be at all mitigated by the proposed change in the government of this country; in fact, it appears to me that they would undoubtedly be intensified.

Looking back on the last seventy years, and remembering the progress that Ireland has made, I see no reason to despair of the future of my country. Although, during the first five and thirty years of my life, there was comparatively little change for the better in the condition of the people, since the year 1850 it has vastly improved. Wages have more than doubled; the people are better housed, better clad and better fed. In recent years, this improvement has been even more marked and, if nothing untoward arises to retard its progress, if (is the hope too sanguine?) Ireland can cease to be “the battlefield of English parties” it will, I trust, ere many years, be as happy and contented as any part of our good Queen’s dominions.

Back to Index

The family of William Richard Le Fanu [100] and Henrietta Victorine Barrington [101]

notes supplementing T.P. Le Fanu’s Family Memoir

by William Le Fanu (1990)

William Richard, Henrietta Victorine, their ten children and the first of their daughters-in-law

In 1990 William Le Fanu (1904-1995) wrote some notes supplementing the Le Fanu Family Memoir, mainly on the large family – eight sons and two daughters – of his grandparents William Richard Le Fanu, a successful railway engineer and author of ‘Seventy Years of Irish Life’, and Henrietta Victorine Barrington. The notes also cover the descendants of WR’s elder brother, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, the novelist and writer of ghost stories.

William Le Fanu wrote about people he knew – his parents, uncles and aunts – and he had an eye for significant detail. The notes, with an introduction, footnotes and genealogy by Julian Le Fanu, are available to read here.

Back to Index

Henry Frewen Le Fanu [118]

(1870–1946)

by J. H. M. Honniball

(Australian Dictionary of Biography)

Archbishop Henry Frewen Le Fanu

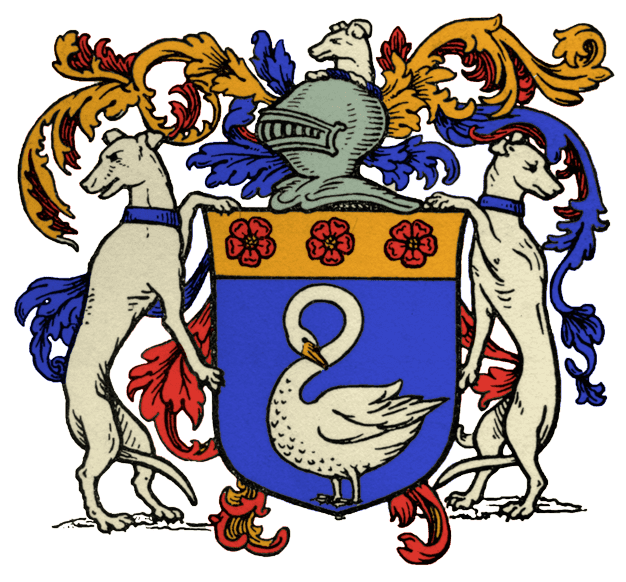

Henry Frewen Le Fanu (1870-1946), archbishop, was born on 1 April 1870 in Dublin, sixth of ten children of William Richard Le Fanu, civil engineer, and his wife Henrietta Victorine, daughter of Sir Matthew Barrington, 2nd baronet. The aristocratic Le Fanu family had migrated from Normandy, France, as Huguenot refugees in the late seventeenth century; in Ireland they shone in church, state and the arts. Armorial bearings assigned by the French king in 1595 were confirmed in 1929. Henry attended Haileybury School and Keble College, Oxford, where he took a second-class honours degree in modern history (B.A., 1893; M.A., 1901); he excelled at Rugby and boxing. After training at Wells Theological College, he was ordained in 1895. He was curate at Poplar, East London, until 1899, resident chaplain to the bishop of Rochester in 1899-1901, and chaplain to Guy’s Hospital, London, in 1901-04.

On 25 October 1904 Le Fanu married Mary (Margery) Annette Ingle Dredge, a vicar’s daughter. Having been appointed archdeacon, he reached Brisbane on 5 January 1905, a fortnight after Archbishop Donaldson. For five years Le Fanu was also sub-dean of the pro-cathedral and on 21 September 1915 was consecrated coadjutor-bishop. A forceful right-hand man, he managed diocesan business skilfully, and as warden of the Society of the Sacred Advent guided the sisterhood’s educational and hospital work.

In 1929 Le Fanu became second Archbishop of Perth, succeeding C. O. L. Riley; he was enthroned in St George’s Cathedral on 19 December. Advantage had been taken of the six months interregnum to appoint an experienced local clergyman as dean of Perth in which post Riley himself had acted since 1925. Holding that the cathedral statute and other legislation passed by synod in August 1929 were ultra vires, Le Fanu soon sought, unsuccessfully, to amend the diocesan constitution. Later, when relations with the parishes became strained over their financial obligations, he defended the Church’s episcopal structure by reminding parishes that the diocese was the prime unit of the Church’s organization. For nearly seventeen years he wisely shepherded a cohesive diocese and worked harmoniously with lieutenants such as the likewise Irish-born R. H. Moore, who was dean throughout, with parish clergy, lay officers and other denominations.

Le Fanu further displayed his financial and administrative acumen during the long years of Depression, drought and war. He recognized that, as financial support from England declined, his diocese must become self sufficient. Concerned for the distressed wheat-belt parishes, he devised a scheme which relieved them of growing debts; however, several parishes had to be amalgamated. Fifty-one buildings were added to the diocese’s equipment in his first ten years; fourteen churches were consecrated during his episcopate and eleven buildings licensed for public worship. They included a university college, a private girls’ secondary school, and a missions to seamen institute, all of which opened in 1931. His largest venture was the Mount Hospital, Perth, acquired in 1934 and extended in 1939.

Le Fanu improved both the architectural standards of churches and the quality of clergy. Though he had no local theological college, he recruited sufficient clergy and saw the proportion of graduates rise during his episcopate; 23 of the 29 men ordained in the 1930s were born or educated within the State and the diocese supported many of them during training in Adelaide. Le Fanu recruited others when in England for the Lambeth conference of 1930 and the coronation in 1937. While the later war years brought improved finances, including contributions to missions, they depleted the staff; over a quarter of the clergy served as full-time padres, and half the country parishes were vacant at war’s end. When the armed forces requisitioned several Church schools and the girls’ orphanage, alternative accommodation had to be found for the evacuees in the country.

Though he had been acting for twenty months, by virtue of seniority, it caused surprise when the bishops elected Le Fanu primate of Australia in March 1935. His abilities and Australian experience were considered more valuable than retaining the primacy’s traditional attachment to Sydney. The vote was also a censure of the exceptionally ‘low church’ mother diocese for its long obstruction of efforts to establish a constitution for an Anglican Church in Australia which would be legally independent of England. Le Fanu valued the honour and was amused that Western Australians were ‘extremely pleased’ about it despite their campaign for secession from the Federation. He received a Lambeth doctorate of divinity in 1936 and was made a sub-prelate of the Order of St John of Jerusalem.

As primate Le Fanu grasped big issues, and was forthright and liberal in his actions and pronouncements. Publicly he was purely a vocal churchman, holding that the Church should be a leavening influence in the community rather than a pressure group in politics. Though he probably never considered himself a socialist, he favoured social change and propounded radical views on many social and economic questions. By 1941 he relinquished his duties as chaplain-general of the Australian forces to bishops nearer defence headquarters in Melbourne. While firmly supporting the war effort, he deplored the persecution of communists and applauded the allies’ growing accord with Soviet Russia. He was an early participant in planning for post-war reconstruction.

The primate also worked assiduously for Church unity, though hampered by distance. His chairmanship of two of the normally quinquennial general synods in 1937 and 1945 won unstinted praise; shunning retirement, he hoped to lead the Australian contingent to the postponed Lambeth conference of 1948. In his seventies, heart trouble scarcely diminished his vigour and his busy schedules; he died in harness, suddenly, on 9 September 1946 and was cremated.

Having been a widower since 1926, on 26 July 1941 Le Fanu had married Winifred Maud Whiteley (d.1979), who had helped to raise his family. He was survived by her and by the three sons and three daughters of his first marriage. His portraits, by Leon Hogan, hang in St George’s College and in the Le Fanu wing of Wollaston College in Perth.

Big in frame and strong in character, Le Fanu was also humble, sensitive and rather shy. He could be incisive with ready wit, but was always quick to apologize for hurt. Even when he provoked controversy, he caused little rancour. His virtues far outweighed any shortcomings. Deeply spiritual and intensely human, he was an ideal Church leader in difficult times.

Back to Index

William Le Fanu & Elizabeth Maconchy

William Le Fanu [127] (Obituary)

Alan Webster, The Independent, June 7th 1995

William Le Fanu

Amongst the select few dedicated to be medical librarians, William Le Fanu was one of the most quietly distinguished. Only appearing in Who’s Who as the husband of the composer Dame Elizabeth Maconchy, he served for nearly 40 years as librarian of the Royal College of Surgeons, in London 191929-68). His many specialist publications included a bio-bibliography of the vaccination pioneer Edward Jenner (1951), Betsy Sheridan’s Journal (1960, reissued 1986), a catalogue of Jonathan Swift’s library (1988) and a study of the writings of Nehemiah Grew (1990). He also translated the Latin works of Sir Thomas Browne for Sir Geoffrey Keynes’s complete edition.

Billy Le Fanu was descended from a Huguenot family who had escaped from Catholic persecution in France to tolerant Dublin. Though always feeling himself Irish, he was one of the first members of this family to work in England. After Eton and King’s College, Cambridge, and a brief spell of teaching he became assistant librarian of the Hellenic Society in 1927, and moved to the Royal College of Surgeons two years later. Under the auspices of the Rockefeller Foundation he undertook in 1937 a survey of London’s medical libraries, and proposed co-operative reorganisation.

The surgeons’ college with its library was destroyed in the Blitz, but Le Fanu had evacuated the books and, in addition to his work as an air raid warden and member of the Home Guard, organised the supply of periodicals to Army and Navy hospitals. While the college was rising from the ashes he threw himself into the development of medical libraries in the United Kingdom and North America. He was chairman of the meeting of the International Congress of Medical Librarians in London in 1953, and vice-president of the meeting in Washington in 1963. He gave valuable assistance to medical libraries at the Royal College of Nursing, the Osler Library at McGill University and the Royal College of Physicians in Dublin, and was an examiner and lecturer at University College London School of Librarians. Never robust, this slim, smiling figure was always at hand with shrewd experienced advice based on a rare knowledge of books, scientific and classical, in English and other European languages.

His quiet satisfaction in his Huguenot ancestry led him to become President of the Huguenot Society (1956-59) and Chairman of its publications committee (1959-79). He was proud of a portrait of one of his ancestors who, as a small child, had escaped hidden in an apple barrel. His breadth of interests gave him many admirers. As a member of the Linnaean Society, he was a keen naturalist and at his Essex home planted an orchard with an unusual variety of fruit trees.

Sharing Dean Swift’s criticism of the treatment of the poor, Le Fanu was a radical in his politics, questioning inequalities of wealth in contemporary Britain. In matters of faith he shared the tolerant humanist attitudes contained in Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici. He valued the ministrations of the parish of Eaton, in Norwich, and during our conversations in his last weeks he told me, with a whimsical smile, that his mind was not acute enough to grasp all the doctrines involved in Holy Communion.

He was devoted to his wife Elizabeth Maconchy and her career, delighting in her prolific musical achievements and sharing her admiration for Vaughan Williams, and was always at hand to assist her in every way. She predeceased him by five months, and he was buried beside her, attended by the care and affection of his children and grandchildren.

Elizabeth Maconchy [127a]: An Appreciation

Hugo Cole, November 1986

Elizabeth Maconchy

Elizabeth Maconchy began to write when she was six and never had the least doubt that her vocation was to be a composer. Not surprisingly, her first pieces were mainly for piano. She grew up without access to gramophone or radio. When she arrived at the Royal College of Music, to study first with Charles Wood, then with Vaughan Williams, she had only once heard a symphony orchestra, never a string orchestra, or a late Beethoven quartet.

As a composer, she continued to search out her own way. Courage and persistence were needed, particularly for women. She won prizes and scholarships but was denied the much sought-after Mendelssohn Scholarship: ‘If we give you the scholarship’, Sir Hugh Allen told her, ‘you will only get married and never write another note’.

In due course, she was awarded the Octavia Travelling Scholarship and went to Prague, where she studied with Jirak. Here, her first major work, the Concertino for Piano and Orchestra, was played by the Prague Philharmonic Orchestra in 1930 and was well received. Her orchestral suite The Land was put on that summer by Sir Henry Wood at the London Proms, and received staggeringly good press notices. In the same year – as Sir Hugh had prophesied – she married William Le Fanu.

But neither marriage, a severe illness, which disrupted her career in 1932, nor the cares of raising a family, brought an end to her writing. The need to conserve her strength and the lack of opportunities for composers of large-scale works may even have been blessings in disguise, since they encouraged her to concentrate during two decades on chamber music, and particularly on the series of quartets which is central to her output. The first was played in 1933 at one of the Macnaghten concerts (almost the only series to provide a London platform for young composers in the 1930s, at which Britten, Rawsthorne, Lutyens and many others first came to public notice); the second, at the Paris ISCM Festival in 1937; the third, at a BBC contemporary music concert in 1938. Concerts of her chamber music were given at Cracow and Warsaw in 1939.

Her thirteen quartets, written between 1933 and 1984, provide an obvious starting point for any discussion of her aims and idiom. There are certain obvious parallels between her music and that of Bartok, which she discovered in her student days and has loved ever since. The language is primarily contrapuntal, involving counterpoint of rhythms as well as of themes. Motives tend to be short and compact, often turning back chromatically on themselves. Development sections concern themselves with a few themes and their transformations. Much use is made of close canonic processes, often used, as in Bartok, to generate new harmonies and textures.

Elizabeth Maconchy wrote three chamber operas; for The Three Strangers, she provided her own libretto, based on a Hardy’ short story. Ander Porter declared the opera to have ‘the directness, the powerful simplicity, the honesty of Hardy’s own work’. The opera The King of the Golden River is notably successful the use made of a cast including adults and children – always a tricky proposition. It was broadcast by the BBC in 1976. In the Little Symphony of 1981, written for the Norfolk Youth Orchestra, she thinks herself into the minds and fingers of young performers in ways which are both imaginative and practical; rhythms are strong and explicit, instrumental families are deployed in clear-cut contrasts, soloists are given the chance to shine while technical demands are kept within reasonable limits.

Elizabeth Maconchy has never been a composer to wear her heart on her sleeve. But (as in Ravel’s case) a dramatic theme or a poem that appeals strongly to her can draw her a little out of herself to reveal aspects of her inner nature. The Cantata Héloïse and Abelard (1970) could almost be described as ‘opera manqué’; a work of Italianate passion and intensity using large resources boldly and directly to achieve the greatest possible dramatic impact. At the other end of the emotional scale, the song cycle My Dark Heart (1982), based on J M Synge’s translations of Petrarch, deals in intimate, half-articulated thoughts and desires. Here all grows from the poems, the music being so discreetly scored that not a syllable of the text need be lost. the moods and inflections of the words are shadowed, anticipated, or prolonged by the six instruments of the chamber ensemble. Gerard Manley Hopkins and Thomas Traherne are among other poets who have similarly drawn from her a personal, and unique, response.

Back to Index

Brinsley Le Fanu [128]

(1905–1964)

a passion for motor racing

Brinsley Le Fanu, racing his Lera at Phoenix Park, Dublin:

Sketch by S. D. Campbell 1938

Richard Brinsley Sheridan Le Fanu (Brinsley) (1905-1964) was the last Le Fanu – and the only one of his generation – to make his career in Ireland. Like his father and grandfather, he was an engineer. He was a partner in Le Fanu and Ekins, a thriving garage business in Dublin with a special line in customising cars for road races and international car rallies. His passion was for motor racing, which he was fortunate in being able to combine with his work. After racing motor cycles with his younger brother Lewen (1906-2005), he moved on to race successfully on the Irish, UK and European circuits. He was President of the Leinster Motor Club, one of the oldest motorsport clubs in Ireland and still going strong.

Brinsley had a very happy married life with his wife Dorothy (née Duncan). They had one daughter, Adrienne Stuart, and three grandchildren. His granddaughter Heather Forland writes:

‘My grandfather raced under the moniker ‘Paddy Le Fanu’ after being called this at an early race in England. I remember the cupboards full of trophies that my grandmother did not enjoy cleaning! In one of his final races in the late 1940s he met a young Stirling Moss, who – like him – had been at Haileybury and who was just starting out on the racing circuit. He became his mentor for the early part of his career and a life-long friend.’

‘Motor racing in the 30s and 40s was a skilled and dangerous pursuit and Brinsley was very successful at it.’

Back to Index

John Lewen Le Fanu [129] (17 July 1906 – 6 April 2005)

An appreciation by his son-in-law Richard Temple Fisher

John Lewen Le Fanu

Most of the family here are blood relatives of Lewen, whereas Bill and Anne Marie and I are simply lucky enough to have married into the family. It is as something of an outsider that I presume to speak of Lewen, who was before all else a family man. He lived very much for his immediate family of course, his wife, Margery, and his daughters, Clare and Juliet. Later he took huge pleasure in his grandchildren and, for the last two years, his great-grandchild. But his sense of family was wider than that, coming from a family all of whom bearing their surname are related to each other. Perhaps back in France there are Le Fanus who are not related, but Lewen’s ancestors left there around 1700 and ultimately came to Ireland, where, as in England now, all Le Fanus are related. With this background, little wonder that to Lewen a fourth cousin twice removed was to be seen as a close relative – I don’t even know who mine are! – and as he became the senior member of the family he always retained a close interest and affection for all current Le Fanus, wherever they might be.

His own early years were spent in Ireland, where he moved from one house to another, according to where his father, a civil engineer, was currently building a harbour or a railway. Term time was spent in England after he was 13, at Haileybury and then at Clare College, Cambridge (hence his omission of the letter ‘i’ when he was registering his daughter Clare’s birth!), but his youthful years were spent in Ireland and it is notable that he and his only sibling, his brother Brinsley (the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s two sisters had married two Le Fanu brothers in the final quarter of the 18th century and a cousin had married a third) – he and his brother Brinsley became a formidable pair of ‘boy racers’ – well, not quite boys, but racers they were, riding motor cycles in the TT on the Isle of Man, and Lewen at one time holding the Irish record for the class of bike he rode.

When life became serious Lewen went to Edinburgh to lodge with his aunt Dora and train to be an accountant. His mother’s family had, and still have, their ancestral home at Crackaig in Sutherland, so he was completely at home in Scotland. He played rugby football during these years, and had the good fortune to be taken on when he qualified as an accountant by John Calder, a great character and owner of Alloa Ales. Lewen started his career then, and it required no alteration other than moving with his boss and being promoted. Thus he followed John Calder to Burton-on-Trent when Alloa Ales was sold to Ind Coope and rose to be director of that firm and was later on the board of Allied Breweries and Guinness when they joined the group.

Lewen’s marriage derived more from his Irish years, as he married in 1937 if not the girl next door, then the girl down the road, Margery Brew, whose father, blind after the First World War, was GP for Bray in Co. Wicklow. They were to be together for no less than 67 years, but first the 1939-45 War saw Lewen in the RAF and posted to remote Stornoway to keep track of American planes by radar and see that they turned right and didn’t fly straight on to German-occupied Norway, while during these years Margery had to care for the newly-born Clare in Stirling.

Their long sojourn in their house at Repton, Derbyshire started in 1947, when Lewen had come out of the RAF and rejoined the brewery. Setting up house and raising his family – both of which gave full scope to his dexterity in repairing things or constructing delightful toys – , working endlessly in his beloved garden, acquiring nicer and nicer cars (and often travelling in them in the furthest corners of Europe), finding time for some fishing, thoroughly enjoying his job and becoming a keen race-goer – originally because his job of Sales Director so often took him to race meetings where Ind Coope was running the bars – , plus the social life at which he and Margery excelled filled his life for the next 25 years, and they were to go on living at Repton for a further 25 years after that, before they both entered their 90s and moved to Abbeyfield House in Rugby. He was driving, and doing the weekly shopping, until he was 93, and keen to go out for a Guinness or a pub lunch until he was well over 98. His retirement years were the ones when the marriages of Clare and Juliet led to the great interest of grandchildren and to Lewen and Margery’s frequent visits to their homes in Rugby and Canada.

Throughout his life Lewen was, before perhaps anything else, a great collector of stories and later a raconteur of these stories, to the great delight of all who heard them. I can vouch too that he seldom repeated the same stories, unless asked for, and that right to the end he was capable of producing the most wonderful stories that one had never heard him tell before. They were delivered with a deft turn of phrase and rich vocabulary that were testimony perhaps to his Irish ancestry, and this gift he kept right up to the end, even when the words stopped being the ones he was actually looking for. I leave you with just one of these stories, which is typical of the sense of absurdity and irony that pervaded so many of them, his tale of Rannoch Moor...

A fitting way, I think, to sum up what we will remember so clearly of you. God bless you, Lewen.

Back to Index

Admiral Sir Michael Le Fanu [138]

Richard Baker

Dry Ginger (Author’s preface)

W.H. Allen 1977

Admiral Sir Michael Le Fanu

Of the many remarkable men who have achieved high rank in the Royal Navy since World War Two, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Michael Le Fanu was perhaps the least orthodox. His premature death from leukaemia in 1970 deprived the nation of a Chief of Defence Staff who would have brought to the supreme Defence job an exceptional humanity and common sense, and who would no doubt have championed the cause of the three Services with the flair he had already shown as a tri-service Commander-in-Chief in Aden during the critical period of the British evacuation.

Michael’s two years as First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff certainly boosted the Navy’s morale. Such was the tonic effect of his personality that even the abolition of the rum ration – perhaps the most controversial and most publicised event during his time at the top – took place without dampening the enthusiasm of the Service, and without diminishing the sailors’ regard for a boss who cheerfully shouldered the blame by assuming another nickname: ‘Dry Ginger’. It reflected his red hair and ready wit and provided an apt title for his book.

Most of those who knew Michael, even as a small boy, could see that he was likely to do something outstanding. He was a born leader. Militarism left him cold, but as a young Lieutenant in the cruiser Aurora he proved his potential as a commander of fighting men, a potential which was never put to the test after the war – though the withdrawal of British forces and families from Aden in 1967 with minimal loss of life must surely count as a notable achievement.

In this, as in so many other situations, Michael displayed a democratic style of leadership that was entirely his own. He dealt with men at every level in a direct way which often bypassed Service conventions and shocked those who liked to abide by the book. One day, discarding his badges of rank, he went down to the dockside in Aden to help a party of soldiers who were loading a store ship. He greatly relished being told by the NCO in charge to ‘get a move on there, Ginger!’.

Michael Le Fanu was a complex man, and to think of him merely as a ‘fellow of infinite jest’ would be quite wrong. Among other things, he was the author of the initial plan for Britain’s Polaris submarine building programme – by far the most ambitious building project undertaken by the Navy since the last war, and one which was carried through with exemplary efficiency.

There was obviously a good deal of the actor in Michael, who loved the theatre and made a habit of collecting performances of Hamlet. He read enormously (‘anything except rubbish’), visited art exhibitions as well as race meetings, walked with his daughter up the Thames to its source and rode a bicycle to Admiralty board meetings. During the last months of his life, he took a course in bricklaying and navigated the lower reaches of the Thames by solo canoe. All these and many other diverse activities grew out of his prodigious energy, and an irreverent sense of fun which no doubt owed something to an Irish father and a mother brought up in the pragmatic atmosphere of the Australian outback.

If there was a touch of the Australian in Michael’s manners, he was no less influenced by America. In 1945, at what was perhaps the crucial stage of his career, he was British liaison officer to Admirals Halsey and Spruance during the final stages of the war in the Pacific, and the experience profoundly affected his outlook. He saw at first hand how decisively the United States had taken over world command of the seas from the Royal Navy and was among the first to face that reality.

But it is not enough to remember Michael Le Fanu in naval terms alone. Although he was dedicated to the Royal Navy (he really did love ‘the Andrew’) his wife and three children remained in the forefront of his mind, whatever the changing demands of his career. Prudence Morgan – ‘Prue’ – the girl he married as a young Lieutenant-Commander in 1943 – was severely disabled by polio contracted when she was seventeen and still at school. To Michael, this was ‘no problem’ and throughout their life together it was never allowed to become one. The wheelchair went almost everywhere and, where it would not go, Prue went in Michael’s arms – into boats, ships, aeroplanes and helicopters, or into the sea on bathing expeditions. Whatever the circumstances, both of them coped with Prue’s disability in a way which created universal admiration, and enhanced the affection so widely felt for them both.

In the later stages of his career Michael inevitably spent a number of years in Whitehall, and there are those who think he was not at his best in the corridors of power. That he was impatient with the endless intrigues of politics is certainly true, and some politicians found him intractable. But, others argue, wasn’t that just what he should have been? In their view, the fact that politicians found him awkward to handle was yet another point – and a substantial one – in Michael’s favour. Whatever his relations may have been with those above him, and he himself realised he was ‘better loved downwards than upwards’, there is no question of his achievements in the final years of his career for the Navy itself.

Back to Index

In memoriam

Anthony Le Fanu [139]

killed in action, March 3rd 1944

BACKGROUND

Following the fall of Sicily, the German army commander in Southern Italy, Field Marshall Albert Kesserling, ordered the preparation of a series of defensive lines between Naples and Rome to delay the northward advance of the Allied forces. The most formidable was the Gustav line in a rugged mountainous terrain of deep ravines and fast flowing rivers dominated by Monte Cerasola and beyond it, the heavily fortified town of Monte Cassino. It would take four major offensives between January and May 1944 before the line was broken and Monte Cassino fell, marked by some of the fiercest engagements of the Second World War with 55,000 Allied casualties and 20,000 Germans killed and wounded.

Anthony Le Fanu (son) writes:

“My father was the senior Sergeant Instructor at the Regimental HQ at Bury St Edmunds and turned down a commission preferring to see action with his men. His regiment, having served in North Africa, was then directed to Italy disembarking at Naples in February 1944. They very quickly moved to Monte Cerasola – the highest peak occupied by the Allies at the time – in bitter weather conditions with only piles of rocks for shelters (sangars), no fires and in close proximity to the enemy.”

The following extract describes the nature of the conflict – similar to the trench warfare of the First World War – and the details of Anthony Le Fanu’s final engagement (from: R.H. Medley, ‘Cap Badge: The Story of Four Battalions of the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment (T.A.) 1939-47’. Pen & Sword 1992).

“The battalion disembarked at Naples on 21st February confident after the recent intensive period of combined operations in Egypt that it was on the way to staging an assault landing somewhere. It was therefore with some surprise it found itself less than forty-eight hours later in the Valley de Sujo, the first staging post on its way into the mountainous country south west of Cassino.

On 27th February, after an exhausting five-hour march up tracks which grew progressively narrower, rockier and steeper, the battalion relieved the second battalion, the York and Lancaster Regiment, on the summit of Monte Cerasola, the highest and most distant feature on this part of the front. It consisted of a long razor-backed ridge of which we occupied one side, just below the ridge, the Germans the other. The mountains were of rock and barren and digging was impossible, the only shelter and protection available being small sangars, built from surrounding rock and bivouacs. It was February and the whole area was under a foot of snow. The enemy greeted our arrival with a ‘Stonk’, which landed directly on Battalion Headquarters, killing both signallers on the brigade set, wounding fourteen others and knocking me out cold.

The opportunities for ground action here were severely limited but a high degree of alertness was essential with the enemy in such close proximity. Great care had to be exercised when moving about the slopes, since the rattle of dislodged stones invariably attracted grenades from the other side. This, of course, worked both ways. A small amount of patrolling around the edges of the position yielded valuable information. Activity was, in the main, confined to artillery and mortar exchanges. These were fairly continuous particularly by night and in the barren setting there was a small but regular daily quota of killed and wounded...

We had a raised plateau to defend. In between ran a deep long gully. Jerry held one half and us the other. At night we had to man the Observation Post with a Bren gun while round the bend separated by a few strands of wire festooned with empty tin cans sat two Jerries with a Spandau [machine gun]. It was eerie, I can tell you. In moments of silence you could hear them coughing. The place reeked of German corpses. In the daytime we used to pull out, then a Vickers machine gun a few hundred yards up the gully would take over and every now and then it would fire bursts down into the gully just in case Jerry decided to visit us. On the ridge our sangars were some sixty feet and in some cases only forty feet from the tip of the crest. We could hear Jerry coughing and bringing up ammunition. Periodically he would throw hand grenades depending how thick the mist was. Number 18 platoon sergeant, Sergeant Le Fanu, waited for the mist to come down and with Corporal Cox ran up to the crest and surprised a group of Germans preparing to attach our sangars. They engaged the enemy, killing some before being killed by Spandau fire. A stretcher bearer, Private Riscom, who went to see if he could help was also shot by a sniper.”

Back to Index

Obituary of Henry Le Fanu [160]

Evening Mail, February 9th 1923

Henry Le Fanu

Henry Le Fanu, B.A., Ex-Scholar of Trinity College, Dublin, Barrister-at-Law, late of the Indian Civil Service.

We record, with much regret, the death, in his eightieth year, of a distinguished citizen of Dublin and alumnus of Trinity College, Mr. Henry Le Fanu. He was a scion of a well-known Huguenot family, long domiciled in the Irish capital, and descended from Etienne Le Fanu, who lived at Caen, Normandy, in the 18th century.

William Joseph Henry Le Fanu was born in Dublin on the 13th of April, 1843, and was the youngest son of the Rev Wm. J.H. Le Fanu, rector of St. Paul’s Church, Dublin. He was educated at the Grammar School, Tipperary, from which he entered Trinity College, Dublin. In the University his career was highly distinguished. A first Honour man in Classics, he won Classical Scholarship in 1863, together with the late Thomas Henry Carson, K.C., the late Sir James Digges La Tonche, Canon James H. Kennedy and other equally able men, who afterwards made their mark in public and professional life.

In 1864, Le Fanu obtained a high place at the Indian Civil Service examination, and shortly afterwards proceeded to the Madras Presidency, in which it was fated that most of his life-work was to lie. Before he went to India he was called to the Bar in both Dublin and London. In India he served as Collector in rotation at Madura, Trichinopoli, Tirupatur and Yercaud. On June 23rd, 1866, he married in St. George’s Cathedral, Madras, Catherine Mary, third daughter of the late William Daniel Moore, M.D., Dublin, et Cantab., of Dublin. By her he had seven sons and one daughter. His wife and most of their children survive him.

After retiring from the Indian Civil Service, Mr. Le Fanu practised as a barrister at Hyderabad. His custom was to come home in the summer of most years, including 1922; but the Indian winter suited him, and he resided until his death at Saifabad, near Hyderabad, in the Deccan.

Back to Index

Cecil Le Fanu [178]: a doctor and a gentleman

James Le Fanu, The Sunday Telegraph, (August 9th 1998)

My grandfather Dr Cecil V. Le Fanu died of sleeping sickness in his home in Bexhill-on-Sea in 1937 at the age of 60. He had been retired from the Colonial Medical Service for almost a decade, having worked continuously for 25 years on the Gold Coast, now known as Ghana.

Cecil left no record, but a few details provide some insight into his life. He graduated from Aberdeen University Medical School in 1899, joined the Colonial Medical Service and left for the Gold Coast in 1902. His baggage included a fine set of surgical instruments – now in my possession – in a handsome wooden box with his name engraved on the top. The scope for practising his surgical skills would have been limited to incising abscesses, setting bones and the like.

His main role, as is made clear in a letter from the Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territory dispatching him to “Navorro for the remainder of the dry season”, was as a public health administrator. His responsibilities included “ensuring an uncontaminated water supply ... causing a slaughterhouse to be built and rejecting unfit animals ... and supervising the dairy arrangements concerned with the supply of milk for Europeans”.

He was, in addition, “encouraged to treat serious cases of sickness among the natives”, which should be “gratuitous, though there is no objection to receiving voluntary ‘dashes’ from grateful patients”.

Cecil stayed “up country” for 15 years, interspersed with home-leave breaks, on one of which he met and married my beautiful Welsh grandmother who returned with him for one tour of duty, after which she came back to England, never to set foot in Africa again. Around 1918 Cecil was posted to Accra, where he became personal physician to the charismatic governor Sir Gordon Guggisberg, and started work on the major achievement of his life: the building of the finest hospital in Sub-Saharan Africa, Korle Bu, on the outskirts of the city.

There are half a dozen photographs from this time, with his inscription in an elegant hand on the back, showing an impressive colonial building with broad verandas and modern, well-ventilated, Florence Nightingale-style wards.

The last two glimpses into his life come from a 1973 publication celebrating the hospital’s golden anniversary, which features a photograph of Dr C. V. Le Fanu dapperly dressed in a morning suit, “discussing medical problems” with a pith-helmeted, white-suited Prince of Wales at the hospital’s opening.

Then there is a short essay by a Ghanaian surgeon, Dr W.A.C. Nanka-Bruce, which includes the following passage: “Dr Le Fanu was a mild-mannered man, tall and debonair and noted for the elegance of his prescriptions. Our paths crossed in June 1925 on board ship when, as fellow passengers in the first class, he was the only ex-patriate to speak to me during the whole of the fortnight of the voyaging to Liverpool. The rest could hardly conceal their resentment at having a ‘native’ in their part of the ship.”

This was his last trip home. He would have been 48, with two young children, my father Richard and his sister Barbara. The family moved to Liverpool, where he joined the staff of the internationally famous School of Tropical Medicine before retiring, prematurely aged, to Bexhill where he died.

There were, in the annals of the Empire, thousands of men just like my grandfather but I am grateful for the few glimpses into his life. He probably viewed his career as unexceptional but, to me, it seems extraordinary. He left behind, in Korle Bu, a fine monument, not just to his own endeavours but to the beneficent principles of British public health and good administration: and, as Dr Nanka-Bruce suggests, despite almost 25 years in foreign parts, at times lonely and very isolated, he nonetheless remained a debonair and civilised English gentleman.

Back to Index

Roland Le Fanu [181]

MAJOR-GENERAL ROLAND LE FANU

From second-class boy, the lowest rank of the Royal Navy, to Major-General, is the remarkable record of Major-General Roland Le Fanu, late of the Leicestershire Regiment, who has just been appointed to command a Territorial Army Division.

Major-General Le Fanu is a member of a well-known Dublin family. He is a son of Mr. Henry Le Fanu, a Dublin man who had a distinguished career in the Indian Civil Service, and Mrs. Catherine Mary Le Fanu, sister of the late Sir John Moore. His grandfather was the late Rev. H. Le Fanu, Dublin.

Major-General Le Fanu is a cousin of Mr. Thomas Philip Le Fanu, of Abington, Bray, a former Commissioner of Public Works in Ireland.

“THAT TIGER SAHIB.”

The General’s career reads like a page from a novel and is a record of brilliance, ability, courage, and tact. As an administrator his unusual methods led to a Government inquiry when he was a young man. This was at Bellary, India, where to-day they still speak in tones of awe of “that tiger sahib Le Fanu,” who smashed graft, eradicated neglect, and devised punishment for the erring which brought them to ridicule. The title “Tiger” referred to the nickname of his regiment, “The Tigers,” and the silence with which he struck.

The result of the inquiry was an expression of appreciation by the Governor-General of India of “young Le Fanu’s outstanding work in face of great difficulties.”

He was brought to England by his father, who had original ideas on a boy’s upbringing, from school in Germany when he was 14. Apprenticed as an engineer to a Glasgow firm, he later left to join the Navy.

Young Le Fanu then joined the Royal Irish Fusiliers, and had risen to the rank of corporal before being commissioned in the Leicestershire Regiment. With only 18 months’ service as an officer he was appointed station officer and magistrate at Bellary, securing the appointment through the second junior officer of his battalion because he was the only one with a thorough knowledge of Urdu.

Stories of the General, who is a legendary figure in his regiment, are legion. Among them is a story of how in his younger days when he desired to improve his educational background he secured an appointment as assistant schoolmaster and spent his time teaching himself as well as his charges.

Born in 1887, Major-General Le Fanu has been on Staff duty since 1917.

Back to Index

Sir Victor Le Fanu [193]

Serjeant at Arms in the Commons

Obituary: Tam Dalyell MP, The Independent, February 9th 2007

Sir Victor Le Fanu

George Victor Sheridan Le Fanu, soldier and parliamentary officer: born 24 January 1925; Deputy Assistant Serjeant at Arms, House of Commons 1963-76, Assistant Serjeant at Arms 1976-81, Deputy Serjeant at Arms 1981-82, Serjeant at Arms 1982-89; KCVO 1987; married 1956 Elizabeth Hall (three sons); died London 5 February 2007.