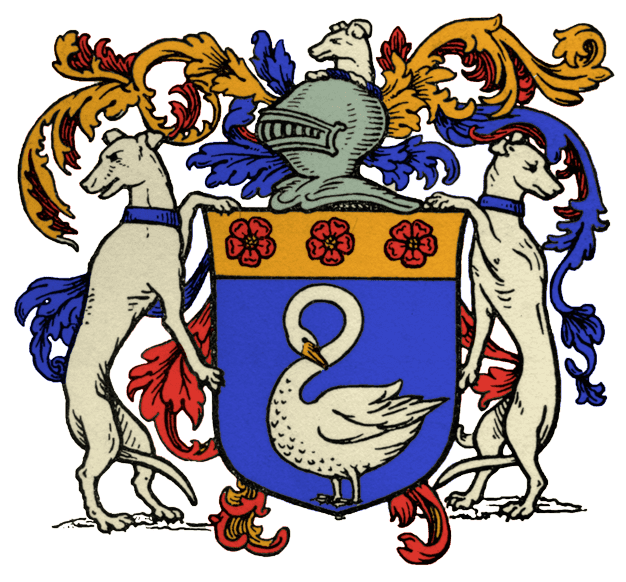

History of the Le Fanu Family

Index

- The Le Fanus – A Brief History

- The Le Fanu family in France: Those Who Left, Those Who Stayed

- Le Fanus in the Landscape of Normandy

Le Fanus in the Landscape of Normandy

by Mark Etienne Le Fanu

The Le Fanu family when the name first emerges in the written record in the fifteenth century were inhabitants of the Calvados region of former Lower Normandy, first at Vire, 60 kilometres south west of Caen, and then, during the sixteenth century, in Caen itself, the region’s capital, and its surrounding communes, where, during a brief period of prosperity in the early seventeenth century, we apparently owned substantial properties. During the Easter weekend of 2023 I went to look at some of the places that are mentioned most frequently in the family Memoir to see what they look like now, in the twenty-first century. The journey was brief (though, thanks to my French hosts, immensely enjoyable) and, although there were revelations, a number of questions concerning the activities and historical status of the family remain unresolved. So what follows is an interim report on this landscape. There is more exploration to do. The places we looked at were Mondeville, Caen itself, Cresserons, Bréville, Basly and Douvres. (Montbesnard, a hill outside Vire that lends its name to the oldest of the family “titles”, was too far away to visit on this trip.) The Guidebook referred to in the text is in fact a major work of collective scholarship: Le patrimoine des communes du Calvados, in two stout volumes issued by Editions Flohic in 2001.

Mondeville

The rather grand title Seigneur de Mondeville held in succession by our direct ancestors Louis (born 1622), Etienne (1625 – imprisoned for his beliefs in the 1670s), Etienne’s son Philippe (born 1681) and finally Philippe’s son Guillaume (born 1708) does not appear to have had any large corollary in landholdings. We are told that the family property here amounted to about 46 acres leased from the Abbey of Fécamp, consisting of two houses plus some gardens and orchards, for which was paid an annual head-rent of “twelve livres, fourteen sols, four deniers, two chickens and ten eggs”. Little chance of finding evidence of these modest holdings (supposing traces of them still exist) in the modern commune which, while still largely rural right into the nineteenth century, has long since been subsumed into the city of Caen where it functions as an industrial zone full of standard factories and modern commercial enterprises. But the old centre is still there, and is not unattractive. A splendidly austere church built in the 1930s with an enormous tower dominates the main street, at the far end of which there is an elegant belle époque mairie. Along with two further churches (the Église Notre-Dame des Prés and the Église Saint-Denis), there are even a couple of still-standing châteaux which historically belonged (they are now owned by the municipality) to families named de Penart and de Tillonbois de Valleuil. Further research would be needed to see what relation, if any, these presumably Catholic aristocratic houses entertained with our own Protestant forbears in this region. Might there have been, in years past, more than one “seigneurie” attached to a given location simultaneously (one of these titles Catholic, the other Protestant, for example)? It is, as will be seen, a question – if not quite an anxiety – that comes up again in some of the other Le Fanu villages we visited.

Church (1936) in the centre of Mondeville

Caen

The city of Caen is handsome, despite its being subjected to substantial allied bombing during the war. The main Gothic and Romanesque churches – St-Jean, St-Pierre, the Abbaye aux Hommes and the Abbaye aux Femmes – seem to have survived largely unscathed along with a number of picturesque old streets and houses. Meanwhile, there has been a huge amount of very modern development, a lot of it (such as the new library designed by Rem Koolhaas in the old port area) of fine architectural quality. It’s an interesting place. The Le Fanu family owned houses here in which they lived, and others from which they collected rents, according to the extant will of Pierre Le Fanu (1580-1627), though alas in which streets is not specified. The Protestant church at which they will have worshipped in the quarter known as Bourg l’Abbé (behind the Abbaye aux Hommes) was destroyed at the Revocation (1685), its ruins enfolded into an area that currently houses a convent. We were able to wander around. The present Protestant Temple, some distance away in the Place de l’Ancienne Comédie, is of modern provenance (1960s I should guess): it was closed on the Saturday we visited. Fortunately, the wonderfully flamboyant Église St-Pierre in the centre of the city was open, and within we came across the simple font at which in February 1708 (a little while before they left for exile in England) Philippe Le Fanu de Mondeville and his wife Marie suffered the indignity of having their son Guillaume baptised according to the Catholic rites. At this stage in the persecution of Protestants, it was that or nothing at all!

The font in Église St-Pierre

Near St-Pierre stands the similarly imposing Église St-Jean, and we saw this too (one of its towers has been picturesquely truncated). It was the (unnamed) priest of this church who, sometime in the mid-1660s, ambushed Philippe’s father, the long-suffering Etienne (“seized him by the throat” apparently), as he set off on a journey to have one or other of his two young children (Etienne junior or Michel) baptised in the by then more welcoming next-door city of Bayeux. Catholic vexation of Protestant rights was, inevitably perhaps, the key theme of our visit. We looked for traces of the notorious Maison de la Propagation de la Foi in which kidnapped Protestant girls – such as Madelaine and Marie, the two children of Cyrus Antoine Le Fanu (1669-1738) – were forcibly brought up in the Catholic faith, but although the street, rue Guilbert, remains clearly signposted, the building itself has vanished. (Happy ending to this story: released as adults, both girls, it is said, quietly resumed the faith of their ancestors.)

Due to time pressure we were unable to visit the city’s Protestant cemetery in the middle of the Jardin des Plantes (where incidentally the English dandy Beau Brummel lies buried).

There are questions that might be clarified here on a future visit. Reformed-faith cemeteries were outlawed in 1685, along with existing Protestant Temples: if you wanted to be “buried Protestant”, it had to be in private ground until well into the late 18th century. Cyrus Le Fanu, as I mention in the accompanying article to this piece (“The Le Fanu family in France” – see above) was interred in the family grounds at Cresserons. But his wife Madelaine Le Sauvage who survived him by eighteen years, was buried in 1756 in what the Memoir describes as “the garden of a Protestant neighbour in Caen, the sieur de Précourt”. I have a feeling that it is this plot of private land that eventually became the “official” Protestant cemetery mentioned at the beginning of this paragraph, but another visit will have to be made to confirm this.

The splendidly flamboyant Catholic church of St-Pierre

Cresserons

Cresserons is a small hamlet (population 1,170) lying a few kilometres north east of Caen and just south of the Normandy beaches where the Allied forces landed in June 1944.

Approaching the village from Caen alongside flat yellow fields of clover and rape, you get a sense of the Channel’s nearness well before being able to spot the sea. The village itself consists of farms and large manors along an axis of two intersecting streets. A number of the houses aligning these roads are enclosed by handsome impenetrable walls of pale Norman stone: one had to squint through their gates to get a glimpse of the buildings. The “noble fief” of Cresserons had been bought by Pierre Le Fanu in 1618 from a certain Isabeau de Sens, but having no advance idea which of these properties housed the family mansion (“chateau”? – perhaps), we allowed ourselves to wander into the grounds of the first large farm we came across in the centre of the hamlet.

Our nice farming friend M. Buhours is somewhat doubtful about our quest.

Here we were met by the owner who came out to greet us, mistaking us for tourists who had lost our way. When I explained to him I had come in search of traces of my ancestors his scepticism knew no bounds. The famous French shrug went into overdrive. After a bit, however, he calmed down and became positively communicative. His family, named Buhours, was the oldest in the village, having inhabited the farm in whose forecourt we were standing for over two hundred years. (The barn indeed had an inscription dated 1800 – the very year in which the Le Fanu family finally lost possession of the Cresserons fief.)

Stone arch on the barn belonging to M. Buhours, inscribed “1800”

His forbears had made their name in horse-breeding – sculpted horse heads decorated the gates of the farm, and annual trophies at the Deauville and Vincennes race courses are apparently still named the Cresserons Cup. No, he did not know the name Le Fanu; as far as he knew, the family who had historically lived in the chateau were called de Basly (this is interesting, for reasons I will come to). The place we were looking for was most likely the walled property just over the road, lived in for many years by a Madame Gherrak, whom unfortunately he didn’t speak to. Meanwhile, he thought there was a Protestant cemetery nearby; there was certainly a Protestant Chapel, and this we should go and have a look at.

It will be seen that the meeting was more picturesque than strictly useful. There was a shortage of hard facts to play around with. Repeated pressure on Madame Gherrak’s doorbell produced no response; nor was there any sign (here or anywhere else) of the antique portail or gatehouse which our great grandfather Henry Le Fanu reported to be the last standing remnant of the mansion when he visited the village on a research trip in 1909. So we still don’t know the exact location of the house and grounds we were looking for.

But we did go to see the Protestant Chapel, just up the road, a modest and handsome building plainly belonging to the 19th century. It has now been taken over as a location for the young people of the village to pursue various post-school activities. I asked one of the handful of teenagers who were present that afternoon with their young supervisor at what date she thought the chapel had been built. She replied that she didn’t know exactly, but she was certain that it was very very VERY old!

The Protestant chapel at Cresserons

Consulting our guidebook when we got back to the car we found that it had been built in 1866, but not consecrated for another eleven years due to fierce opposition from the commune’s majority Catholic inhabitants. The guidebook provided several other interesting pieces of information. Over the course of history there had been three Protestant churches in Cresserons, the first destroyed during the late 16th-century wars of religion, the second destroyed in the 1680s, while the third was the one we had just been looking at. (Meanwhile the village’s medieval Catholic church, the Église Saint-Jacques, some distance away, had been restored as early as 1610, just eight years before our family moved into the village.) In fact the guidebook had a number of interesting remarks about the confessional history of the commune, especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including for example that “under the influence of Cyrus Le Fanu” the number of Protestants actually increased in the 18th-century

malgré les exactions Catholiques

(“in spite of Catholic persecution”). This suggests to me that Cresserons may have functioned as a sort of miniature redoubt protecting the Reformed faith in this area during the early post-Revocation period. Yet what is clear is that Protestants were never in the majority, and that there would always be Catholic opposition to them. By 1866, when the last of the three Protestant churches was constructed (against opposition, as I say above), the village housed a mere 85 Protestants out of a population of 641 inhabitants.Just to remind ourselves: We know from the family Memoir that the Cresserons domain was sold on to new Protestant owners as late as 1800. The family into whose possession it fell, Le Mayne de Sante-Marie, were still owners in 1877, when the then incumbent built a Protestant cemetery within the grounds of the mansion. At some time in the future it would be interesting to go back and have a look for this. One piece of caution, however, emerges from the guidebook: Les erreurs des bombardements américains dans la nuit 6 juin 1944 détruisent une partie du château (“Errors in American bombing on the night of 6 June 1944 destroyed part of the mansion”). How much or how little survived of “our” building remains to be seen.

High walls round the manor houses in Cresserons discourage enquiry

Basly

Basly is not far from Cresserons; it is likewise a small and prosperous village. None of the documents cited in the family Memoir claim that the Le Fanus were “seigneurs” of Basly; there is nevertheless a distinct feeling of family connection.

The Protestant consistory from which Etienne Le Fanu was expelled in 1656 for marrying a Catholic wife (in a Catholic church) was located in Basly. If we remember that our friendly farmer thought that the surname of the local grandee in Cresserons was “de Basly”, it’s interesting to discover (from the family tree) that in 1608 Pierre Le Fanu’s sister Marie did actually marry the current Sieur de Basly, Samuel Le Mière, described in the document as a man of substance and “Conseiller du Roy”. (Their son Jean in due course became brother-in-law to Samuel Bochart, one of the most famous Protestant theologians of the age. Readers are urged to look him up in Wikipedia. In 1667 this eminent divine and humanist, friend of Queen Christina of Sweden, died of a heart attack on the floor of the Academy of Caen “during an impassioned debate with Huet on the translation of a passage of Origen relating to transubstantiation.”) Basly has apparently always had a strong Protestant connection: part of its seventeenth century population was made up of incoming Swiss Calvinist evangelists whose descendants may still be living in the district. The guidebook informs us that a Protestant temple was constructed here in 1685 – rather late in the day, perhaps, for such optimistic building projects (indeed it was destroyed immediately afterwards). And there is apparently a Protestant cemetery situated within private grounds – we weren’t able to discover which – whose last grave is dated 1844.

Meanwhile the Catholic church of St-Georges is a small Romanesque jewel. And there are a number of beautiful mansions in the vicinity, elegantly restored. The village was liberated by the Canadians in June 1944, who are commemorated with flags and some movingly inscribed plaques.

Bréville

Bréville is situated a little to the east of Cresserons, on the other side the Pegasus Bridge across the Caen canal, scene of fierce fighting in June 1944. The village itself was the scene of bloody action between the German army and British parachutists on the nights of 5th and 6th June, and again between June 8th and 12th, when defending German troops were finally routed in engagements initiated by a combined force of the 5th Highland infantry, the (American) 6th Airborne division, and No. 6 Commando. This is all commemorated in placards situated in the middle of the large village green. Not surprisingly, there was widespread destruction. The old medieval church has been obliterated, replaced by a not unpleasant modernist construction designed (perhaps) by the same architect responsible for the impressive edifice dating from the mid-1930s that we saw earlier in the day in Mondeville. Four Le Fanu ancestors are described as being Seigneurs of Bréville in the family tree: Charles de Cresserons (who went into exile and fought for King William in Ireland); his brother Louis (1622-1685 – more about him later); Louis’s son Henri (mentioned as “Sieur de Bréville” in a legal document dated 8 November 1691) and finally this man’s cousin Jacques, whose date of birth we don’t know but who died in exile in Ireland in 1740. Surprisingly (if disappointingly) the guidebook we had begun to rely on is quite specific in not mentioning Le Fanus! Certainly the last will and testament of Pierre Le Fanu, already mentioned, signed and witnessed on 12 February 1626, states clearly enough his intention to leave to his descendants maisons et heritages assises paroisse de Bréville but according to the guidebook, the title of Seigneur was in the hands of the Venoix and Le Brun families. This they retained during the bulk of the seventeenth century, when it was sold on to a certain Abbé Bigot, in 1693. (The title became a marquisate in 1762, before being abolished at the French Revolution.) So while it is clear that Le Fanu ancestors owned land here, it is not quite so clear why they were entitled to designate themselves as the sole feudal occupiers of this commune. As I said in my remarks about the Mondeville estate, it is possible that the title of Seigneur could be valid simultaneously in more than one family. Whether the precise designation (Sieur or Seigneur) is a legal term, or one of mere social custom, I feel that somebody living must know the answer. It shouldn’t be too difficult to settle the matter authoritatively.

Douvres

We stopped at Douvres on the way to Cresserons. Mentioned quite frequently in the Memoir, it lies only a few kilometres away on the same coastal road that cuts across the top of this section of Calvados, with wide open fields on either side and the distinctive smell of sea in the air. The commune is in fact a quite substantial small town, furnished with an enormous 19th-century basilica, Notre-Dame de la Déliverande, whose all-of-a-piece interior carries the authentic mark of that epoch’s Catholic religiosity. While it was open (and we had fun looking round) , the earlier medieval Église Saint-Rémi in rue du Presbytère, was shut: a great pity, because it is in this church that we would have had the chance to stumble across perhaps the only existing Le Fanu tombstones remaining in France. Buried in the nave of this church are Charles Le Fanu, Sieur de Mesnil (1678-1737) and his wife Marguerite Agnès Le Hantier de la Bourdonnière. Of course, to be buried in a Catholic church, they would have to have been Catholics themselves, so somewhere along the line this couple would need to have abjured. And it appears that this is what in fact happened. Charles was son of Louis Le Fanu, mentioned above, the “weakest” Protestant link among the eleven children of stalwart Pierre Le Fanu, the family patriarch. Louis’s wife, Louise du Bourget, had renounced her Protestant faith early, in a ceremony conducted in the Église Saint-Pierre in Caen (that flamboyant Gothic masterpiece mentioned above whose font I photographed) on 25 June 1675, fully ten years before the Revocation; and although, interestingly, her son Charles was nevertheless baptised according to R.P.R. rites in 1678, all their six children, including Charles, were brought up, after 1688, as nouveaux (or nouvelles) catholiques. The wedding between the couple Charles and Marguerite took place in 1704, and is nicely if accurately described in the marriage certificate as fait au plaisir de Dieu en face de notre mère l’Église catholique, apostolique et romaine. Like his similarly-abjuring cousin Jean-Louis (who came back from exile in England in 1684 to serve in the Navy of Louis XIV), Charles died Catholic, en fidèle chrétien, [ayant] recommandé son âme à Dieu par l’intercession de la glorieuse Vierge Marie, Saints et Saintes du Paradis (the words on his tombstone).

What conclusions to draw from this journey? First, the nobility of Protestantism in France, which is the nobility of all lost causes. France is, or was, a Catholic country. While certain heroic individuals like Cyrus Le Fanu held out as long as possible (encouraging his descendants to do the same) it was always easier to abjure if you wanted to survive and prosper as a citizen. I am struck by the poignancy of the eighty or so year intermission granted by the Edict of Nantes. Although the Huguenot cause was spread right across the country (very strong in the South as well as in Normandy), there weren’t finally enough of us to prevail. After the suppression of the Fronde – aided by great Protestant generals like Turenne – it was only a matter of time before the monarch decided to act against his other potential rebels. What hadn’t been accomplished by the sixteenth-century Wars of Religion was finished off with remarkably little bloodshed. The failed rebellion of La Rochelle proved a portent, as did its aftermath. Richelieu and his successor Mazarin were both of them kind to Protestants by the standards of the age, but the existence of the cult was still an anomaly in the body politic. The magnificent fact of an official policy towards tolerance was only ever going to be an episode. Retrospectively, Protestantism probably had to go. In the course of it, only dear Etienne (as I think of him and after whom I am named), was actually flung into jail. The non-apostasizing Le Fanus who remained in France merely fizzled out slowly. In exile in England and Ireland, the family found new vigorous pathways – though that too came to an end. To be Protestant in modern Ireland – after enjoying the privileges of the Ascendancy – was surely another lost cause! Now it is all over anyway. Indeed, I had to pinch myself occasionally, in the course of this research trip, to remind me that I myself and my siblings were brought up Catholic. I feel that I belong to both confessions. Yet also – at other times – to neither.

April 2023

Back to Index